He wrote home asking for treatises on metallurgy, urban and agricultural hydraulics, piloting steamboats, naval architecture, powders and saltpeters, geology, and masonry, as well as a pocket book of carpentry and manuals of glassmaking, brickmaking, earthenware, metal-forging, candle-making, and gun-making. By December he had crossed the Gulf of Aden and was in Harar, in Ethiopia. But Rimbaud’s ideas for world-transformation involved more than coffee. In August 1880, he arrived in Aden, and began working for Alfred Bardey, a coffee trader. He was now twenty-one-and converted to the adult world of business. It was also the last time, it seems, that Rimbaud considered himself a writer. This package was the last time Rimbaud saw his Illuminations.

But as Verlaine left, Rimbaud handed him a package of manuscripts to be delivered to Nouveau, who was to arrange for their possible publication. It was the last time they would see each other. He stayed two and a half days, was altogether sensible, and upon my remonstration returned to Paris to go, straightaway, to study over there on the island. Three hours later he had renounced his god and reopened the 98 wounds of Our Savior. By February 1875, he was gone again, this time to Stuttgart-where Verlaine, out of prison and now converted to Catholicism, came to see him: Verlaine arrived here the other day, clutching a rosary. Rimbaud remained in Britain until the end of the year, when he went home to Charleville. Nouveau stayed until June, then went back to Paris himself. In March 1874 he returned to London, accompanied this time by another young poet, Germain Nouveau. Verlaine was sent to prison, while Rimbaud went back to Paris. The affair of the Foolish Virgin and the Infernal Bridegroom culminated in July 1873 in Brussels, when Verlaine shot Rimbaud in the wrist. In the autumn of 1872 they moved to London-offering French lessons, drinking, learning English, reading in the British Library, hanging out with the exiles from the Paris Commune, and attending lectures and arguments in Soho pubs: hipsters in the city of Karl Marx. Verlaine invited him to Paris, and so began the next episode in Rimbaud’s mythology. That autumn, the obscure seventeen-year-old prodigy wrote to the poet Paul Verlaine-ten years older and settling into married life-asking for help. Rimbaud lived-with momentary escapes-in Charleville until 1871. The family became his first experiment in world-description: Mama, “whose slip smelled sharply,/Rumpled and yellowed at its hem like fruit” Papa, with his “pants/My finger wanted to pry open at the fly” and a sister with “a mawkish thread of urine” escaping “from her tight pink nether lips.” Sure, this occurs within a poem that is a parody, but it represents a diagram of Rimbaud’s future writing: a family is where you are schooled in desire and the repression of desire-in shame and disgust and boredom, all the varieties of entrapment. “In all the world,” wrote Rimbaud, “no more moronic, provincial little town exists than my own.” His father abandoned the family when Rimbaud was six-leaving him to the stern presence of his mother and the careful presence of his sisters. He was born in 1854 in Charleville, in northern France.

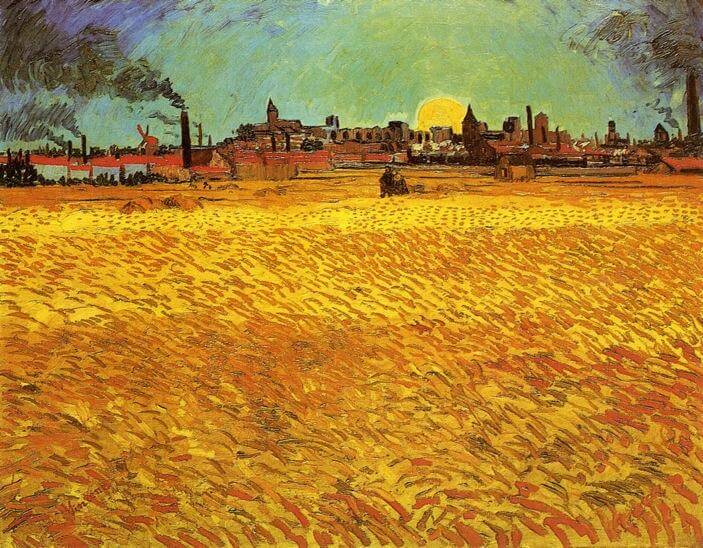

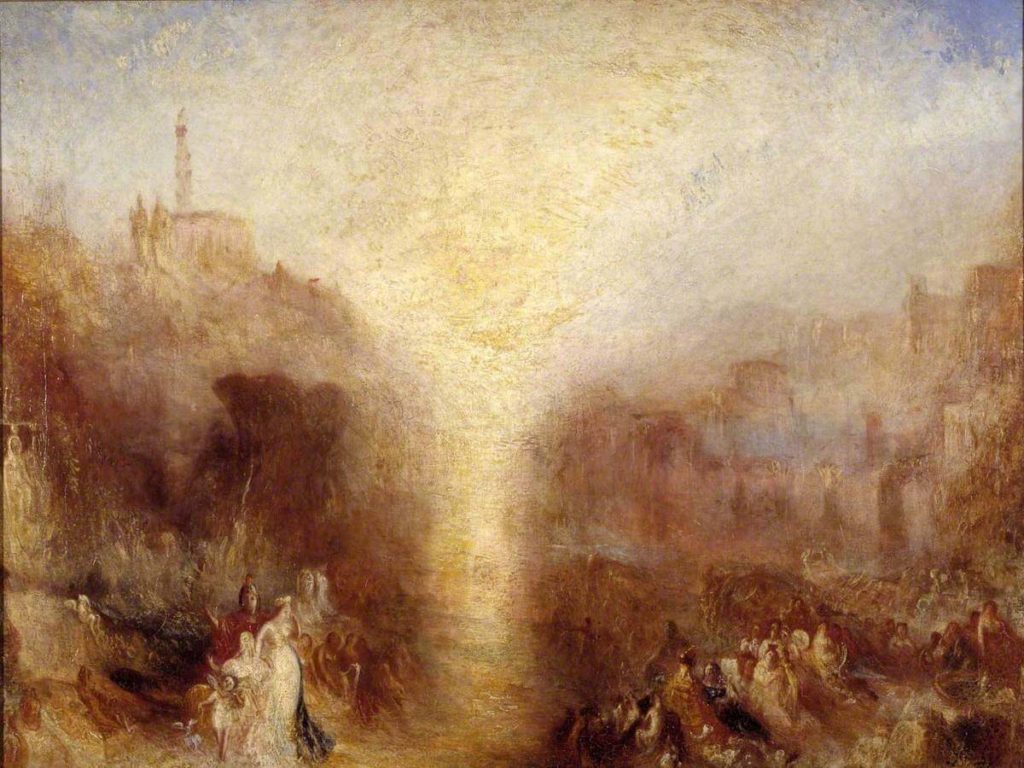

Illuminations rimbaud series#

There is something oppressively neat about the manner of this death: his life had always been a series of canceled escapes. He had five years to live: he died in 1891, from cancer of the knee, in a Marseilles hospital, trying to arrange for a boat back to Ethiopia. The poems in Illuminations began to be published about ten years later, in 1886, without Rimbaud’s knowledge-when the poet, now thirty-two, was living in Harar as a trader.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)